The lost skill of 'just figuring it out'

Examining technology's cultural rubicon (and some professional anecdotes) to understand why some people know how to 'just figure it out.'

Here is a NotebookLM podcast summarising this essay, which is funny irony if you read the entire piece.

When I was a work-study student at university, my manager taught me the single most valuable skill I could have for the next twenty years: figuring it out. If I wanted to do something I’d never done before, someone else on the internet probably already had, and I just needed to find that person.

That was back in 2006, but this lesson is reflected in Google Search results now, with ‘Reddit’ as the most common search query suffix. I used to joke that my most valuable professional skill is that I can Google things faster than others—it was even my LinkedIn headline for a year (I didn’t need a job then). For a short time, we were all really good at Googling things. Until, for some reason, we had to start clapping back with ‘Google is free’ or ‘Google exists’ because that was no longer our default behaviour when we needed to learn something. Why? WHY, I ASK!

The Napster factor and converting PDFs

I am not here to start a generational argument, but I often ask whether someone could burn a CD if required to do so today. And to answer your immediate question, yes. I am fun at parties.

I don’t ask this during interviews because it can be ageist, nor is it meant to be a gotcha to make someone feel dumb. I genuinely want to know how much context I need to give you when I explain something technical.

There are three answers: yes, no, and probably. I am a ‘probably’ because I’d need a little refresher. ‘Probably’ means you will ‘just figure it out’, and that attitude transcends generational access to this dated technology. If I’m explaining how to use a CRM, a ‘probably’ will know how to find and read documentation.

Installing Napster or Limewire, searching MP3 file types, downloading multiple files to test download speeds, and then burning them onto a physical object would be considered a highly technical skill nowadays. With the advent of iTunes as a music library and then Spotify as a streaming service, this skill is no longer relevant at the surface level. But remember, we learned how to do this without Reddit and just a nascent version of Google and the internet where Wikipedia’s existence was ‘insider knowledge’ and considered unreliable. In short, we just figured it out.

Many people like me don’t understand how we developed this skill to just figure it out, so we might get impatient with our friends, parents, and colleagues when they don’t have it. To make a broad generalisation, Boomers never bothered to learn how to convert a PDF file because they were in management positions during the technology rubicon. They had Gen X and Millennials do it for them. But what surprises people is that Gen Z never had to learn. We think young people learn technical literacy through osmosis, but that’s not true. Boomers asked us to convert their PDF files. Gen Z has “save to PDF” as a native feature.

Everyone is firing Gen Z

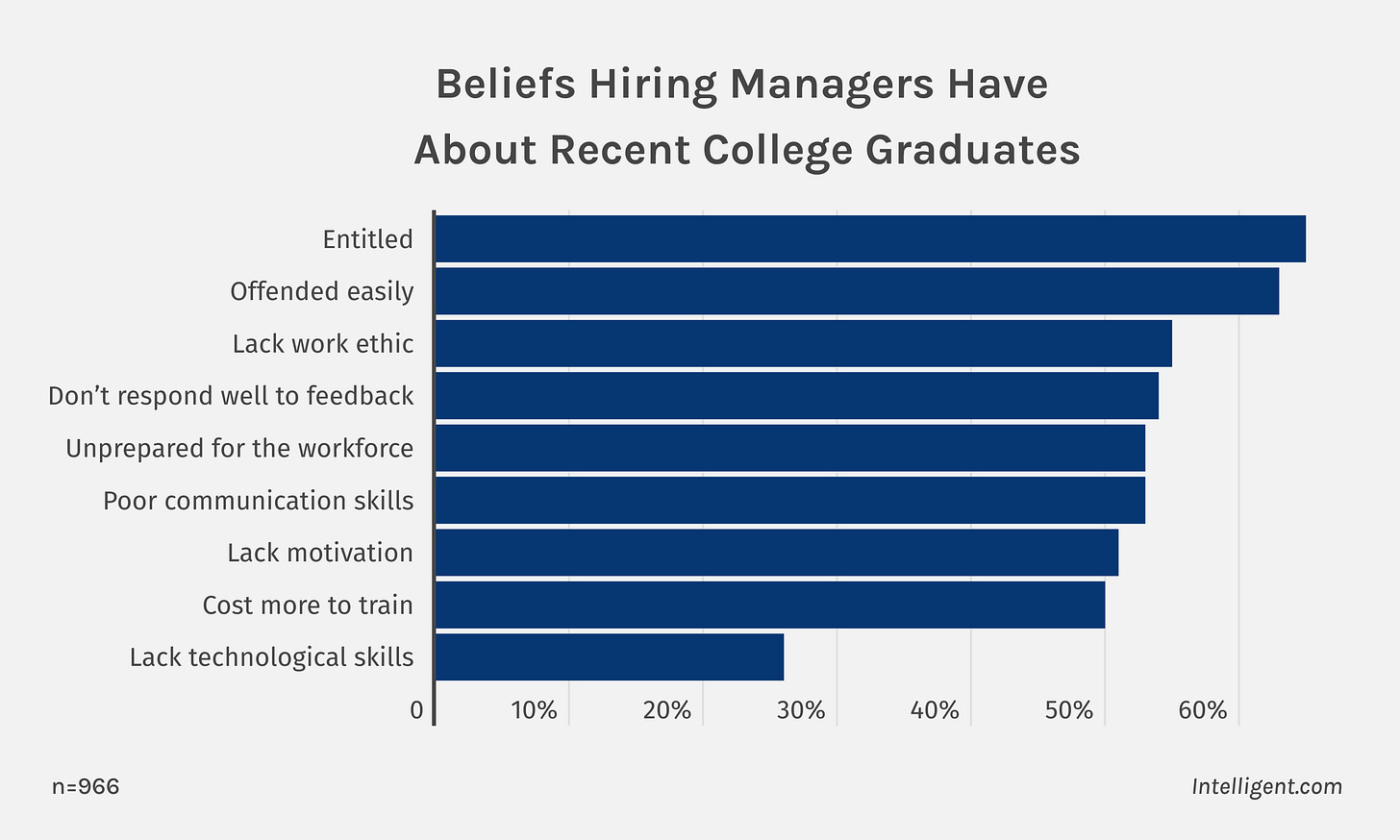

A Fortune article1 went viral because it cited a study on how new grads are being sacked at an alarming rate. My knee-jerk reaction was that of any 30-something: Yeah, that makes sense. My other Millennial and Gen X friends talk about this all the time, careful not to morph into cranky old people who think kids these days are rude, have no work ethic, and need a reality check.

The Fortune article and the study2 it cites do just that.

The study aimed to determine how schools and employers can help new grads prepare for professional settings. They accept that Gen Z has an attitude problem and needs university-level networking and e-mail writing courses. The Forbes Article quotes a Cisco executive, David Meads:

“…attitude and aptitude are more important than whatever letters you have after your name, or whatever qualifications you’ve got on a sheet.

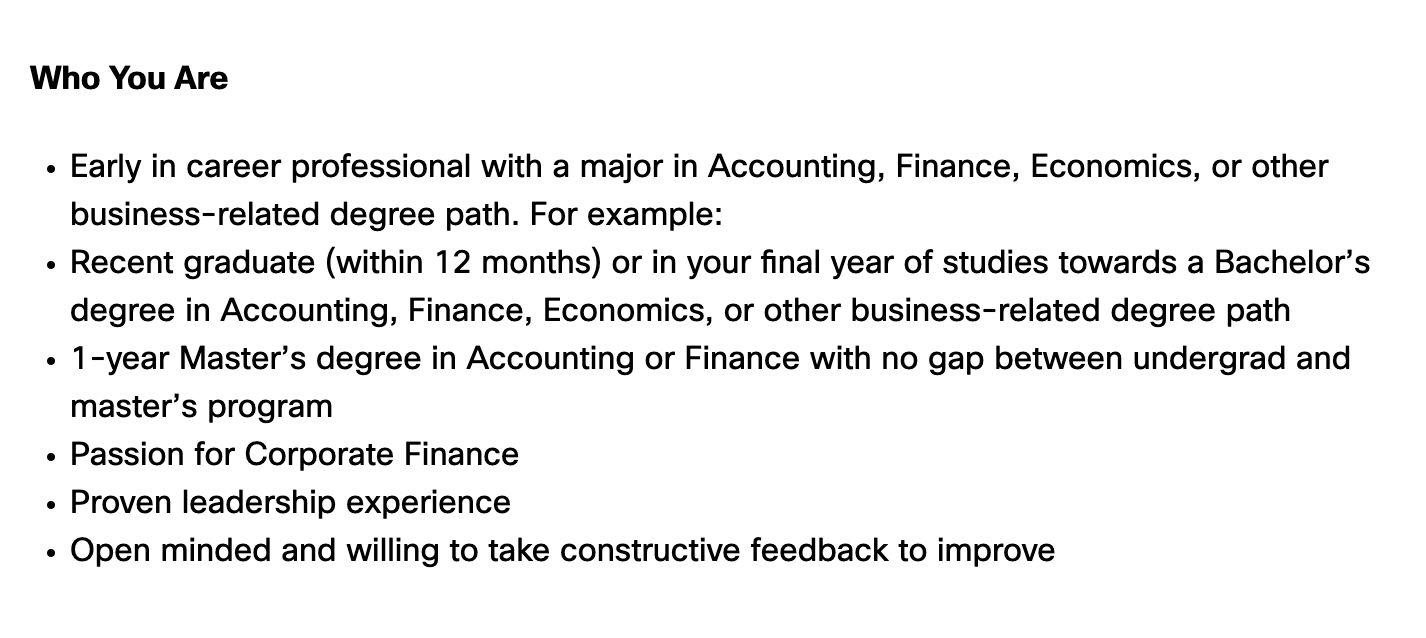

That’s odd to say when your company has a whole section for 'Early in career” applicants, with job descriptions like this:

I majored in Anthropology. To answer your immediate question: no, my parents weren’t happy about it. But, hey, maybe I have a passion for corporate finance. Without the letters behind my name, would anyone take a moment to read how I worked in the Business Research Division at Leeds School of Business despite my tragic chosen degree field? I drafted SQL documentation for government research on pharmaceutical spending.

I know the answer: NO. NEVER. NEVER EVER EVER.

But remember the manager I mentioned in the first sentence of this piece? That was at the Business Research Division. He’s the one who taught me how to just figure it out, and I can pinpoint my transition from a charity case worker to a Marketing Operations Manager at a B2B tech agency on that one lesson.

I digress slightly.

I don’t have a problem with Gen Z’s attitude and professionalism. I find it refreshing. When I entered corporate England, I didn’t speak the language, but I knew how to do the job — or figure out how to do it. So, when hearing phrases like, “What’s the estimated lift?” or “Dev build published to staging, deploy to prod.” I had to Google all of it. But imagine my shock when I learned everyone else was in the same boat. It’s such a relief talking about the absurdity of corporate tech-speak to each other, 1:1, but why haven’t we collectively decided to stop it?

I’ve completely digressed.

Remove the smarm3 from the Fortune article, and we’ll still have the problem of workforce unpreparedness. I don’t think schools or employers can address it until they— and here’s the plot twist — talk to an anthropologist.

UX did its job because no one needs to figure anything out anymore

I used to work with UXers, and they are some of the most emotionally and academically intelligent people I have ever met. Their job is to understand how humans interact with the world and eliminate the obstacles that keep people from achieving their goals. My anecdotal observation is that they also have humanities and social sciences backgrounds, such as English lit, psychology, philosophy history, and anthropology. These subjects are research-heavy and require you to digest information from static sources, combine it, and draw a unique conclusion.

In academics, it might look like this:

If A is not B,

And B is not C,

Then is A = C?

Cite your sources.

In UX, it might look like this:

If desktop users are not contacting us.

Desktop users are not visiting the contact page at all.

Can they not find the contact page?

Change the hamburger menu to a full navigation.

Use data to back up your theory.

When I say it might look like that, I mean one of my former UX colleagues wrote a whole-ass presentation on why desktop navigation should not be hidden in a hamburger menu, using Google Analytics charts to support his claims. He was 100% right, and we saw increased conversions when we changed it.

UX and UI designers have applied their academic research skills to the tech industry so well that we no longer need to search for answers. There are few technical obstacles to figure out in everyday life, so what do you do if an answer is not obvious?

You ask. You ask incessantly. You ask before Googling something because the answer should have been obvious. It wasn’t. So you’re pinging me about why an email didn’t show up in your inbox, and I ask if you’ve checked spam, and you ask me how to check spam, and I send you a screen recording of how to find spam in Gmail because it’s inside the expanded inbox menu. Then, I have to write documentation on how to check spam, and I do it by Googling an existing tutorial and saving it to my bookmarks so I can send it to the next person who asks me why they didn’t receive an email.

UX is too good now. That’s all I’m saying. It’s so good, and technical systems are so efficient that no one needs to just figure it out anymore.

I told you this is hard to explain

When you get frustrated with a friend, family member, or colleague, I want you to think about what is frustrating you. It’s not their attitude. The problem is that they will not just figure it out, and likely through no fault of their own4. But, because they weren’t born between 1970 and 1990, they never wanted to make a mixed tape that required they adapt to the technology rubicon in their spare time, between Social Studies and Art History.

The solution here is not to teach classes on writing emails because emails aren’t the problem (unless you ask me why you didn’t receive one before checking spam). The problem is in the very foundations of 21st-century society, moulded and smoothed out into a user-friendly world, where we expect everyone to just know things without understanding how we came to know them. Put simply, we need to understand how we learned to just figure it out.

“Bosses are firing Gen Z grads just months after hiring them—here’s what they say needs to change.” Orianna Rosa Royle, Fortune, 23 September 2024.

“1 in 6 Companies Are Hesitant To Hire Recent College Graduates.” Intelligent, 13 September 2024.

We will not explore weaponised incompetence today. This is already too long.